by Bro. Alberto Parise MCCJ

Imagine being at the helm of a ship. Until a few years ago, we faced one storm at a time: a financial crisis, then a pandemic, perhaps a hurricane. It was difficult, but we knew what we were dealing with. Today, that ship is in the middle of an ocean where five different storms have erupted simultaneously, colliding and feeding off one another. The wind from one drives the waves of another, the rain from a third floods the engine room, and so on.

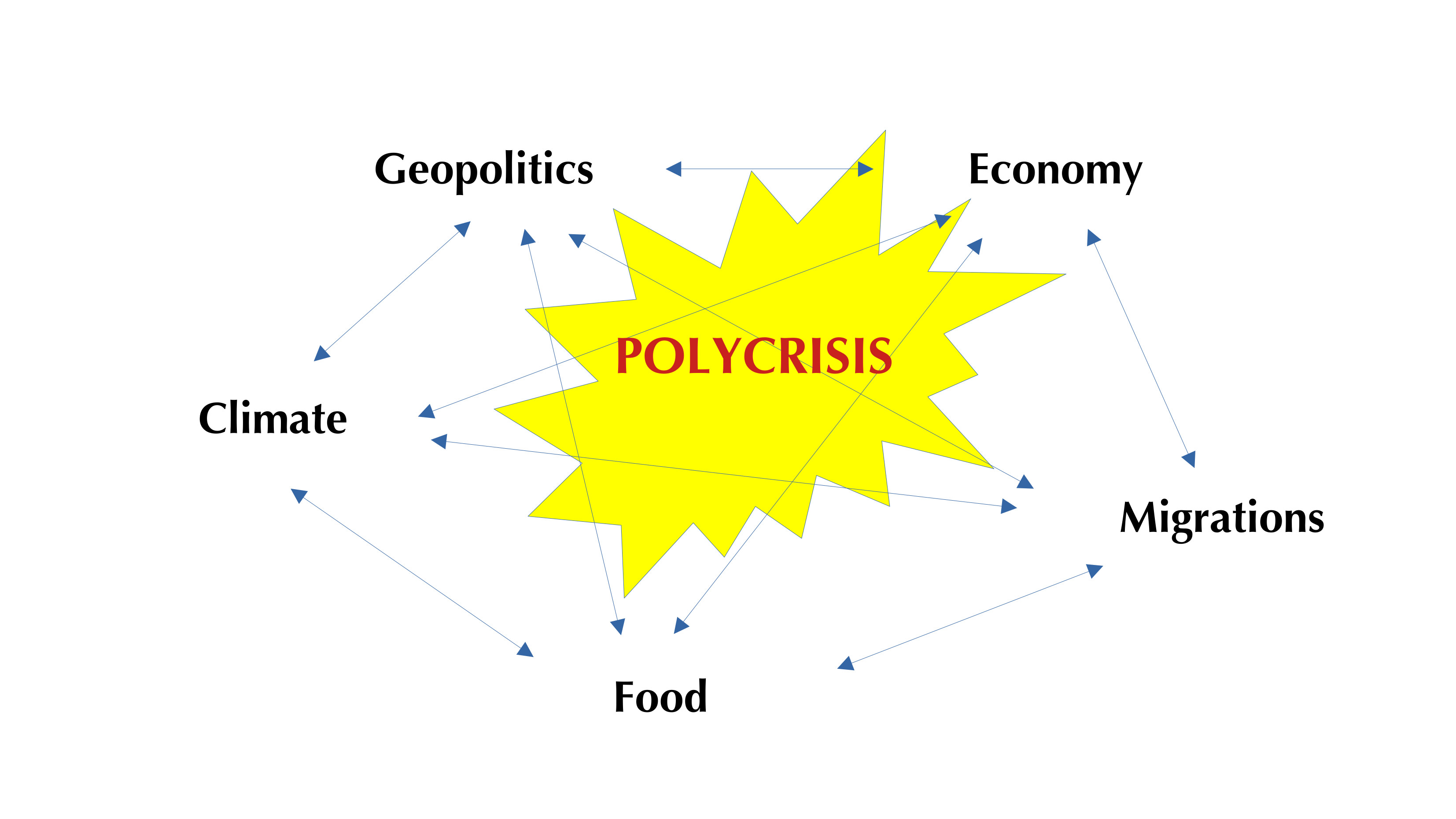

We are no longer living in an era of multiple crises, but in a single, vast “polycrisis.”

This is the concept launched at the Davos Forum in 2023, which we will explore together today. We will understand what it is, why it is different from anything we have seen before, and what its constituent elements are.

I. What Is the Polycrisis? Beyond the Simple Sum of Problems

We often hear it said: “We have too many crises going on.” But the polycrisis is not just a shopping list of problems.

- Negative synergy: crises are not merely adjacent; they are interconnected. They speak to and influence one another. The energy crisis does not remain confined to gas bills; it drives up fertilizer costs, which in turn raise the price of bread in Egypt, fueling social instability with geopolitical repercussions. It is a global domino effect.

- The systems effect: the behavior of a polycrisis system is unpredictable. It is more than the sum of its parts. Addressing a single problem in isolation can worsen others. It is like an IKEA piece of furniture assembled with the wrong instructions: tightening one bolt can cause another panel to collapse.

- The solution paradox: this is the heart of the challenge. Simple solutions no longer exist. Acting on one front without considering the others can be counterproductive. This is the fundamental dilemma of our age.

Let us now analyze the five main elements, the focal points of this perfect storm.

1. The Geopolitical Crisis

The world in 2024-2025 shows a marked increase in geopolitical and military tensions, measured by both rising military spending and the persistence of protracted conflicts: global military expenditure reached ~272,000 billion USD in 2024, a 9.4% annual increase (the highest level ever recorded). Armed and political crises have produced an immense number of displaced people: ~123.2 million people forcibly displaced (end of 2024) and over 117 million by mid-2025 according to UNHCR/Global Trends estimates. This is one of the highest levels ever recorded for the phenomenon of forced migration.

The notion of “Chaosland,” developed by the geopolitician Lucio Caracciolo (founder and director of Limes), is one of his most effective metaphors for describing the post-bipolar contemporary world, particularly in the 21st-century context. According to Caracciolo, Chaosland is the set of areas of the planet characterized by fragmentation, instability, and the absence of a stable geopolitical order.

It is not a single state or a precise geographical entity, but a “mental and political territory” that identifies the condition of the world we live in: an international system in which no power is able to impose a coherent global order. Characteristics of Chaosland:

- End of the Bipolar and Unipolar Order: After the Cold War, neither the United States nor other powers have managed to create a stable system. The world is multipolar, but without shared rules.

- Fragmentation of Power:

- Weak or failed states.

- Competing regional powers.

- Non-state actors (militias, corporations, terrorist groups, NGOs) influencing international dynamics.

- Hybrid and Diffuse Conflicts: No longer “traditional” wars between regular armies, but asymmetric wars, proxy wars, cyber conflicts, and technological competitions. Extensive sanctions, control over critical technologies, trade restrictions, and the use of economic flows as weapons make competition more pervasive and less predictable. On various occasions, Pope Francis has described this state of affairs as a “piecemeal third world war.”

- Widespread Perception of Insecurity: Fear and uncertainty become political tools: powers defend themselves more than expand, and societies live in a state of “permanent alarm.”

- Crisis of Multilateralism and the Rule of Law: The use of force and impunity prevail, with an erosion of human and peoples’ rights, and the fragmentation of civil society.

“Chaosland” is not just a description of reality, but also an interpretative key:

- It is the new geopolitical normal of the 21st century.

- There is no longer a “center” and a “periphery”: everything can become the epicenter of a crisis.

- Europe, in particular, lives on the margins of Chaosland, trying to defend an order it no longer controls.

- The geopolitics of fear (insecurity, competition, disinformation) replaces the classic geopolitics of stable balances.

2. The Economic Crisis

The economic situation in 2025 represents the full maturation of critical trends that emerged in previous years. The world is not experiencing a classic synchronized recession, but a complex scenario of “mild stagflation” (anemic growth + persistent inflation) aggravated by geopolitical fragmentation, with trade and technological wars. We are witnessing the end of globalization as we have known it. The global network is fragmenting into rival blocs.

The Macroeconomic Framework: Sluggish Growth and Persistent Inflation

- Global Growth: The International Monetary Fund, in its updated forecasts for early 2025, revised its estimates of global growth downward to 2.7%, a rate well below the historical average and indicative of prolonged stagnation. The euro area and China are slowing, with growth at 0.8% and 4.2% respectively (the Chinese figure is the lowest in decades, excluding peak pandemic years).

- Persistent Inflation: Contrary to optimistic forecasts, inflation has not returned to the 2% targets. In the euro zone, it still stands at 3.1% (ECB data, first months of 2025), while in the USA it is at 3.4% (Fed data). The so-called “last mile” of inflation has proven to be the most difficult: prices for services, energy, and food remain stubbornly high due to structural rigidities in the labor market and recurring commodity shocks.

- Monetary Policy: Central banks are in an unprecedented dilemma. They have kept interest rates at high levels (Fed Funds Rate at 4.75%-5.00%; main ECB rate at 3.75%) to fight inflation, but are beginning to face pressure for easing to avoid sinking growth. The result is a “higher for longer” policy that dampens investment.

Causes of the Crisis:

- Unsustainable Sovereign Debt: The figure is alarming: global public debt has exceeded 330% of world GDP. Low-income countries are the most exposed.

- The Costly Energy Transition and Geopolitical Fragmentation: The investments necessary for the green transition, although vital, are contributing to inflation in the short term. Costs for renewables, batteries, and critical raw materials (lithium, cobalt) remain volatile. The reorganization of supply chains (“de-risking” from China, “friend-shoring”) is proceeding at a sustained pace. While increasing strategic security, it raises production costs and fuels inflationary pressures. Trade between allied political blocs grew by 6% in 2024, while trade between rival blocs is stagnant (WTO data).

- Systemic Unsustainability: A system that requires continuous growth to sustain itself is unsustainable in a world of finite resources; the system based on capitalization (accumulation) cannot but generate inequality, debt, and socio-environmental impacts with exorbitant costs.

Consequences and Future Scenarios

- Increased Inequalities: The crisis disproportionately affects the weakest segments of the population and low-income countries. The Oxfam Report 2025 estimates that the richest 1% of the global population has captured two-thirds of the new net wealth created since the beginning of the decade.

- Risk of Financial Turmoil: High interest rates have exposed vulnerabilities in the financial sector. In 2024, new crises of regional financial institutions occurred in the USA, and there were tensions in the Chinese and European commercial real estate markets. The “private credit” market (non-bank private credit), now valued at over 2,000 billion dollars, represents an area of opacity and systemic risk. The risk of a new debt crisis in an advanced economy or a large emerging economy remains high.

3. The Climate Crisis: The State of the Climate Today — Key Facts

- 2024 was the hottest year ever observed in instrumental records, with the global average annual temperature on average exceeding the +1.5°C limit compared to the pre-industrial period.

- Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and emissions are at historical highs: atmospheric CO₂ and global energy emissions reached record levels in 2024 (e.g., ~422–423 ppm of atmospheric CO₂ and rising global energy emissions in 2024).

- Oceans getting warmer and sea level rise accelerating: the ocean recorded the highest observed heat content (record 2023–2024) and the global mean sea level is accelerating (recent years with rates above the historical average).

- Arctic ice loss and cryosphere in rapid transformation: the 2025 maximum extent of Arctic sea ice was the lowest in the satellite record; this is consistent with long-term trends.

- Extreme weather events (heatwaves, floods, intense hurricanes, wildfires) are more frequent and severe, and many analyses link the increased probability and intensity of these events with global warming.

Main Causes:

- Human Activities — burning of fossil fuels (energy, transport, industry), deforestation, and some agricultural practices: these activities increase concentrations of CO₂, methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O) in the atmosphere, the main observed drivers of warming. The IPCC states with very high confidence that the observed warming is largely due to anthropogenic emissions.

- Natural feedbacks (e.g., loss of ice reducing albedo, forest stress reducing CO₂ absorption) are amplifying the effects of emissions. Recent reports also indicate signs of weakening natural absorption of emissions (forests and oceans) in some regions.

4. The Migration Crisis

The global migration crisis in 2025 is not an isolated phenomenon but the most visible and humanly dramatic epiphenomenon of the polycrisis. It is the symptom of a world in deep transformation and suffering, where pressures are discharged along geopolitical and economic fault lines. The numbers continue to show a growing trend, despite restrictive policies. According to UNHCR, the number of people forced to flee worldwide has exceeded 130 million (figure at the end of 2024, trend confirmed for 2025). This includes refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons. It is as if the entire population of a large country, like Japan, were on the move. Migration flows are not caused by a single factor, but by an inextricable intertwining of elements: conflicts and instability, climate and economic crisis.

5. The Food Crisis

The 2025 food crisis is not a simple shortage of food, but the result of a systemic failure of the global supply chain, made uncontrollable by the intertwining of the polycrisis. It is a crisis of access and stability, more than just production.

The General Picture

- Acute Food Insecurity: According to the 2025 Global Report on Food Crises (published by the Global Network Against Food Crises), in 2024 over 220 million people in 53 countries/territories faced crisis or worse levels of acute hunger (IPC/CH Phase 3 or above). It is estimated that this number remained at similar or slightly increased levels in 2025.

- Chronic Hunger: The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) reports that progress in reducing chronic hunger has completely stalled. The number of chronically undernourished people has returned to 2015 levels, undoing years of progress.

- Critical Focal Points: The most severe situations persist in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, northern Nigeria, Sudan, South Sudan, the Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali), and Yemen. In these regions, large segments of the population live in conditions of food emergency or famine.

Why the Food System is in Crisis

- Conflicts and Instability (primary factor): Conflicts remain the main driver of hunger, responsible for 60% of cases of acute food insecurity.

- Extreme Climate Shocks (risk multiplier): Extreme weather events, amplified by climate change, are devastating harvests globally.

- Economic Instability and Inflation (crisis of access): Food price inflation, currency depreciation.

Chain Consequences: migration and social instability, child malnutrition, increased child labor.

The international response is in crisis. The World Food Programme (WFP) declared that in 2024 it faced its largest funding shortfall in history, forcing drastic cuts in food rations for millions of refugees and displaced people.

The 2025 food crisis is proof that food security is no longer an agricultural issue, but a geopolitical, climatic, and macroeconomic one. Without coordinated action to resolve conflicts, mitigate the climate crisis, and stabilize the global economy, the number of people on the brink of famine is destined to grow further.

The Anthropological Question

Addressing the polycrisis is a complex undertaking, not only because of the interconnections between the various crises that constitute it, the solution of which requires an integral approach (cf. LS 139). But also, and above all, because the social, economic, and political problems of our time can no longer be understood or resolved solely in terms of structures, institutions, or resource distribution; their deepest roots now lie in a distorted or reductive vision of the human being. For this reason, Pope Benedict XVI in Caritas in Veritate (n. 75) speaks of a fundamental anthropological question as the remote cause of the crises of our time. The idea is this: the ecological and social crisis of the contemporary world stems from the fact that the human being no longer recognizes itself as a creature but claims to be the absolute master of reality. Social problems cannot be resolved only by economic or political measures unless the vision of humanity underlying cultural and technological choices is confronted.

Pope Francis takes up this diagnosis but expands it: the anthropological question is above all a relational, social, and environmental one (integral ecology, culture of fraternity, the fight against the throwaway culture). For him, changing policies without transforming how we conceive of and live our relationships with others and with creation is insufficient. In the encyclical Laudato Si’, Francis states:

The creation accounts in the book of Genesis contain, in their symbolic and narrative language, profound teachings about human existence and its historical reality. These narratives suggest that human existence is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: the relationship with God, with our neighbor, and with the earth itself. According to the Bible, these three vital relationships have been broken, both outwardly and within us. This rupture is sin. The harmony between the Creator, humanity, and all of creation has been disrupted because we have tried to take the place of God, refusing to acknowledge ourselves as limited creatures. This has also distorted the nature of our mandate to “subdue” the earth (cf. Gen 1:28) and to “till it and keep it” (cf. Gen 2:15). As a result, the originally harmonious relationship between human beings and nature has turned into conflict (cf. Gen 3:17-19). [Laudato Si’, 66]

In other words, the harmony between the Creator, Creation, and humanity has been destroyed because we have tried to take the place of God.

The creation and primordial humanity narratives found in Genesis help us to discern the cultural and socio-economic dynamics that characterize our time and to evaluate the meaning of the solutions proposed. Indeed, these solutions inevitably derive from the cultural assumptions from which they are developed.

Relationship with God

In the creation stories emerges a human being who is a creature made in the image and likeness of God. Its vocation is to live like God: in communion, as gift and love. It is a relational creature, and the social dimension is constitutive of humanity. God creates with the Word, which calls to life, to relationship. As a creature, the human being experiences a lack. As noted by Massimo Recalcati, God removes a rib from Adam and does not merely close the wound, but marks it as a lack that constitutes the human as such. He closes the wound not to heal or fill the lack but to make it constitutive, a condition for openness to irreducible otherness.

The serpent’s insidious plan, on the other hand, pushes one to want to reach the same fullness as God, to achieve a life that excludes lack, to transfigure the human into a veritable god, rejecting one’s own finitude, denying one’s insufficiency and lack. Humanity falls into this trap at the moment when it creates a distorted image of God, which entails a distorted image of humanity. The command not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil reveals the constitutive limit of humanity, the impossibility of being the ultimate criterion of reality. In other words, the human is a creature, not the creator of truth and morality. If it claims to autonomously decide what is good and evil, it puts itself in God’s place—and loses itself.

What image of humanity, then, is at the root of the dynamics that have led to the polycrisis? It would seem that of homo economicus: humanity reduced to its productive and consumerist dimension: a rational being that always chooses what is most advantageous, denying its spiritual and relational dimension. Its main characteristics are:

- Instrumental Rationality: Every decision is guided by the rational calculation of self-interest (maximization of utility or profit).

- Radical Individualism: The human is seen as an isolated individual, acting autonomously and independently from others.

- Self-referentiality: The ultimate goal of actions is personal interest, not the common good.

- Isolation of Ethics: Economics is considered “scientific,” i.e., separate from ethical or religious considerations.

- Relationship with Nature: Nature is seen as a resource to be exploited to produce and accumulate wealth.

Relationship with Our Neighbor

In the perspective of homo economicus, the relationship with our neighbor will therefore not be marked by openness to otherness or by reciprocity, but rather will have a predominantly contractual and competitive character. An economy that functions as a permanent competition creates structural victims: “discarded,” marginalized people. This is fertile ground for conflicts and violence, both direct and structural. A system that reduces human relationships to contracts and competition releases—and even legitimizes—a form of “non-recognition”: the other is useful or useless, a competitor or a loser, deserving or waste. As Pope Francis has emphasized in Evangelii Gaudium, this economy kills (EG 53).

Neglecting the commitment to cultivate and maintain a right relationship with our neighbor, towards whom we have a duty of care and guardianship (Gen 4:9)—as suggested by the biblical narrative of Genesis and as the encyclical Laudato Si’ emphasizes—also destroys our internal relationship with ourselves, with God, and with the earth. In these narratives, everything is interconnected, and the authentic care of life itself and our relationships with nature is inseparable from fraternity, from justice and fidelity towards others (LS 70).

When all these relationships are neglected, when justice no longer dwells on the earth, Genesis tells us that all life is in danger. The flood narrative suggests the gravity of such a social situation, to the point of echoing the specter of primordial chaos, in the face of the inability to live up to the demands of justice and peace (Gen 6:13).

Yet, despite human wickedness being great on earth, one upright and just man—Noah—is enough for there to be hope, for God to open a way of salvation, giving humanity the possibility of a new beginning (LS 71).

Relationship with the Earth

A distorted reading of Genesis 1:28 has historically led to justifying arbitrary human dominion over the earth, over Creation, misrepresenting the biblical mandate to care for, guard, and cultivate the earth. Responsibility before an earth that belongs to God requires respect for the laws of nature and the delicate balances among the beings of this world (LS 68). In the perspective of homo economicus, however, the relationship with nature is one of exploitation, seeing in it a resource to be used to produce and accumulate wealth.

The reflection in Laudato Si’ (LS 71) continues by noting that:

The biblical tradition clearly establishes that this rehabilitation entails the rediscovery and respect of the rhythms inscribed in nature by the hand of the Creator. This can be seen, for example, in the law of the Sabbath. On the seventh day, God rested from all his work. God commanded Israel that every seventh day should be celebrated as a day of rest, a Sabbath (cf. Gen 2:2-3; Ex 16:23; 20:10). Furthermore, a sabbatical year was also established for Israel and its land, every seven years (cf. Lev 25:1-4), during which the land was given complete rest, it was not sown, and only what was necessary for survival and hospitality was gathered (cf. Lev 25:4-6). Finally, after seven weeks of years, that is, forty-nine years, the Jubilee was celebrated, a year of universal forgiveness and “liberty throughout the land for all its inhabitants” (Lev 25:10). The development of this legislation sought to ensure balance and equity in human beings’ relationships with others and with the land where they lived and worked. But, at the same time, it was a recognition that the gift of the land with its fruits belongs to the entire people. Those who cultivated and guarded the territory had to share its fruits, especially with the poor, widows, orphans, and foreigners.

The Sabbath, in other words, is the foundation of the sabbatical year and the Jubilee year, with practical consequences of broad scope, in particular:

- The Rest of the Land: This meant liberation from systems of accumulation and exploitation, while promoting the sharing of what divine providence offers for the basic needs of all. When the little that exists is shared, there is enough for everyone. (Lev 25:11)

- The Restitution of Land: Properties that had been sold or transferred were returned to their original owners, ensuring that families maintained their source of livelihood and their socio-cultural identity. (Lev 25:10, 13)

- The Liberation of Slaves: Those who had sold themselves into slavery due to debt were set free, reaffirming the dignity and freedom of every person and recalling fraternity in an egalitarian society. (Lev 25:10)

- The Remission of Debts: Debts were canceled, allowing those who had fallen into poverty to start anew without the oppression of financial obligations. This emphasized the importance of mercy and solidarity, offering everyone a chance for a new beginning. (Dt 15:1-3)

This biblical tradition constitutes a prophetic critique of unjust socio-economic systems and indicates a sense of direction for a more just, fraternal, and sustainable society.

A Change of Pace: COP30 in Belém and Overcoming False Solutions

Right now in Belém, Brazil, COP30, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is taking place, precisely at its thirtieth session. As every year, we observe that climate change and its consequences are becoming increasingly critical—Hurricane Melissa dramatically reminded us of this just a few days ago—but the negotiations often leave us disappointed, failing to provide the answers that everyone and the planet itself need. Naturally, it is a very complex issue from a geopolitical and economic point of view. However, it is possible to discern the cultural roots that block a real turning point: there is an unwillingness to question the capitalist-financial development model, which is based on indefinite growth (moreover unsustainable in a world of finite resources), the commodification of everything, and the maximization of profits for capitalization. All this leads to proposing false solutions, i.e., policies, projects, or technologies presented as remedies to climate change but which do not actually reduce emissions of climate-altering gases (responsible for climate change) on the necessary scale, reproduce injustices, or create new environmental and social damage. They often serve to prolong the use of fossil fuels or to transfer responsibilities from major polluters to local communities.

This is what Pope Francis has defined as the technocratic paradigm, i.e., the dominant worldview of the modern world that considers technology and technique as neutral and autonomous tools, capable alone of solving every human problem, without questioning the values, meaning, and ethical limits of their use. It is the mentality that says “if it can be done, it must be done,” even without asking whether it is right or sustainable, in the pursuit of indefinite material progress. At a philosophical level, consciousness of the limit has been lost: be it natural, ecosystemic, or ethical. Even what cannot be done today may become possible in the future, with the power of technology and the mobilization of adequate finances.

In essence, it is believed that every problem can be solved by an invention or technological progress. And this often becomes an opportunity to create new markets, new opportunities for economic growth. All this goes hand in hand with a strong push towards privatization and the disempowerment of politics: there is a push to leave problem-solving to the markets.

Conclusion

To conclude, I invite you to consider these reflections of Pope Francis, from Laudato Si’ (LS 75):

We cannot sustain a spirituality that forgets God the all-powerful and Creator. In this way, we would end up worshiping other powers of the world, or we would place ourselves in the Lord’s stead, to the point of claiming to trample upon the reality created by Him without knowing any limit. The best way to place the human being in its proper position and put an end to its claim to be an absolute dominator of the earth is to once again propose the figure of a Father Creator and sole master of the world, because otherwise the human being will always tend to try to impose its own laws and interests on reality.