A presentation to the Provincial Assembly of South Africa. Bro. Alberto Parise, MCCJ – 15th April 2021

The parable of a missionary model in a changing world

“What we are experiencing is not simply an epoch of changes, but an epochal change”: with these words, in various occasions (2015, 2019, etc.) Pope Francis grasped the substance of the time in which we are living. It is a change of paradigm, involving new social systems and a new mentality, new cultural horizons. The dynamics of globalization and of the digital revolution, on top of the dominant Neo-liberal financial capitalism, are shaping the world in a radically new fashion.

Change characterises all areas of life and society today. Although new possibilities and potential for the promotion of life are emerging, nowadays the prevailing economic system is leading the world in the direction of social exclusion and environmental devastation, with climate changes having a devastating impact on the planet. For example, the Oxfam 2019 report shows how the gap between the rich and the impoverished ones continues to widen exponentially: the wealth of the world’s 26 richest people reached $1.4 trillion in 2018, which is the same amount of wealth possessed by the world’s 3.8 billion poorest people. The report also explains that, in many countries, acceptable education and basic health care have become a luxury that only the rich can afford. Every day, ten thousand people die because they cannot afford the care necessary to survive. Unemployment and underemployment are widespread globally and people, in many cases, are even beyond the threshold of exploitation and oppression: these people are excluded, they become “waste”, among the indifference of those who are privileged. The other emergency, correlated to this socio-economic situation, is climate change, with serious environmental, social, economic and political consequences. In short, the dominant economic system – evidently colonial in its dynamics – is unsustainable. We need to realise that such a grim picture of reality is not a contingency, but a structural outcome of the global system.

Also from a “religious” point of view, we are experiencing profound changes: religious pluralism is becoming common everywhere, in many cases raising tensions, fundamentalism and identity struggles. Secularism is spreading at a high pace, leading to two opposite perspectives: on one hand, a worldview that rejects the idea of a spiritual reality within the material one; on the other hand, the “spiritualization” of reality and the disengagement from social responsibility. In either case, the “sacramental” value of the world is denied, there is a dichotomy of sacred and profane, spiritual and material, which is the essence of secularism.

Against the backdrop of the profound changes that the world is experiencing, also missionary service is facing new scenarios. The traditional model of mission, a creation of the XIX century, is based on geographical and expansion assumptions, where missionaries are sent as special “corps” from Christian countries to baptise and implant the church in non Christian countries. As far as Missionaries Institutes are concerned, it is based on the idea of “sending” provinces (in the northern hemisphere) and provinces (in the southern hemisphere) that “receive” missionaries; likewise, countries in the South are seen as a territory for “evangelisation” and those in the North for “mission promotion”, to raise the funds to finance missionary service and structures with donations from affluent Christian countries.

All such assumptions nowadays are failing the test of reality. In various African countries, like Kenya and South Africa, over 80% of the population define themselves as Christians (of various denominations), and in countries like DRC, Angola and Rwanda it goes well beyond 90%. Instead, in traditionally “Christian” countries like France, Belgium, Germany and the UK, that percentage falls below 70%, and in the Netherlands even below 60%. Even more significantly, practicing Christians are generally a tiny minority, amid a highly secularized society. Also the geography of vocations is radically different, with most of the missionaries coming from the young churches of the South. Financing missionary ministry is becoming an ever bigger challenge, with the fading away of donations from benefactors in the North. This is pushing Provinces in the South to develop mission promotion activities and starting income generating projects. On the other hand, a greater consciousness of the urgent need for mission in Europe is emerging, as also stated by our XVIII General Chapter. In fact, the boundaries between evangelization and mission promotion are ever more blurred. So much so that in Europe, for example, they do not speak any longer of mission promotion but of “missionary action”, which reflects the fact that evangelization and mission promotion overlap.

The emergence of a new paradigm of mission

In a nutshell, the traditional missionary model finds it difficult to situate itself in the new epoch we are entering, which requires a new paradigm. That model worked very well for a long historical time, it has been a vehicle of grace and, if today we have vibrant young Churches around the world, it is also because of it. We are profoundly grateful for all that. Nevertheless, undeniably reality is changing and it is in the process of overtaking it, as the discussion above argued. This does not happen abruptly and as a Missionary Institute we are making a transition in communion with the Church towards a new paradigm of mission. The synthesis of such elaboration is given by Pope Francis in his Encyclical Evangelii gaudium, his programmatic document to shape the direction of the Catholic Church for the years to come.

Starting with a discernment of the signs of the time, Pope Francis presents a theological reading of the new epoch we are entering in, and suggests a new paradigm of mission. No longer simply geographical, but existential. The Church is called to overcome her own self-centredness and to go forth to all the human peripheries where people suffer exclusion and experience the hardship of economic inequality and impoverishment, social injustice and environmental degradation. All these situations are no longer a dysfunctional aspect of the economic system, but a requirement for the system itself to prosper and continue in its own terms.

Mission, therefore, becomes a paradigm of all pastoral action and the local Church is its subject. So, what is the role of the missionary institutes? It is that of animating the local Churches to live fully their mandate of being missionary Churches that go forth to the existential peripheries.

Pope Francis is re-launching the vision of the Church of the Second Vatican Council, as “the sacrament, or the sign and instrument of intimate union with God and of the unity of the whole human race”. The Church is called to gather a “people” who are able to go beyond the confines of belonging and walk towards the Kingdom of God. Then the Christian testimony to the Risen Lord will be productive and the Church, too, will grow by attraction and not because of proselytising.

The Apostolic Exhortation offers four major criteria guiding the discernment of missionary ministry:

- Reaching out to the peripheries, to the impoverished the marginalised, the excluded. By the way, this is in continuity with the Comboni charism of making common cause.

- Witnessing the kerygma, the communication of the Gospel, which has to do with the “encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (EG 7). Communication, moreover, means that the Gospel is not simply a one-way process but a process in which the listener interacts.

- Prophecy both as denunciation of evil in society (an economy of exclusion, the new idolatry of money, a financial system which rules rather than serves, inequality which spawns violence, hastened deterioration of one’s cultural roots, process of secularization that tends to reduce the faith and the Church to the sphere of the private and personal) and as proposal of constructing alternatives leading to more just and peaceful societies (hear the cry of the poor and struggle for their liberation and promotion, enabling them to be fully a part of society, working to eliminate the structural causes of poverty and to promote the integral development of the poor, as well as small daily acts of solidarity in meeting the real needs which we encounter).

- Evangelising Cultures and inculturation of the Gospel: herethe challenge is to make the missionary presence answer the deep desires of people’s hearts. In the words of the International Commission’s document ‘Faith and Inculturation’, inculturation of the Gospel implies that the “Gospel may penetrate the soul of living cultures, respond to their highest expectations”.

The relevance of the Comboni Charism to the new paradigm of mission

It is rather possible to experience a sort of resistance against the new paradigm of mission. It is understandable that those who have lived a dedicated, generous missionary ministry within the old model of mission may feel a sense of loss, or even of betrayal. However, we need not to confuse a missionary model with the charism of the Institute. In fact, we realise that the Comboni charism is very relevant and appears “tailor-made” for the new paradigm of mission. In the first place we have the central idea of the regeneration Africa with Africa, a concise image that stands for a most complex and articulated story: there is the idea of generating a people who experience communion with God in the Risen Christ and contributes to building up an alternative society, in harmony with the action of the Spirit and the Kingdom of God. The proclamation of the Gospel helps to bring to completion those “seeds of the Word” already present in the cultures and spirituality of the people. Comboni also stressed the importance of this work being “Catholic”, that is to say, universal: far removed from self-reference, he saw himself as an integral part of a much greater and broader missionary movement with a variety of gifts and charisms. There is room and need for a variety of contributions and collaboration that develops in a synodal spirit. All that is central to a ministerial approach.

The central idea of making common cause with the impoverished people resonates with the idea of being at service starting with the peripheries, like a “stone hid under the earth”, opting for an insertion point close to the excluded, side by side with the “crucified” ones (“the works of God are always born at the foot of the Cross”). It is even and especially in the experience of limitations, of sin, of failure that we experience the paschal mystery, together with the people, for a radical transformation that the world awaits.

Comboni saw his role as that of an animator who made an untiring effort to move the conscience of the Pastors of the Church concerning their missionary responsibility so that “Africa’s hour might not pass in vain” (RL9). That means discerning the hour of God, that is the kairos, the transforming action of the Spirit that makes all things new.

In the view of EG, the mission of the Church and all its ministers is directed towards the Kingdom of God, striving to create room in our world where all people, especially the underprivileged and the excluded, may experience the salvation of the Risen Christ.

The option for “specific” ministries

Ministries are of crucial importance as a place of encounter between humanity and Word and Spirit in history. As the geographical criterion becomes less significant, mission ad gentes tends to focus more on human groups, especially those who are at the margins, at the peripheries. A ministerial approach, therefore, would be concerned with finding a good insertion point and developing a customised pastoral approach that goes beyond a generic pastoral work – which is basically the same regardless of where it is situated – and that it is articulated in a plurality of services, under a shared vision and methodology. In other words, we are talking of an organic pastoral approach, in which all dimensions (leitourgia, martyria, diakonia, koinonia) are present and in synergy. That is a complex framework that is possible only when the subject is the whole Christian community, in communion with other communities.

In a nutshell, missionary commitments are focused on services rather than a ready-made missionary kit (or generic pastoral approach); ministry implies that missionary work is necessarily contextualised and depends on people’s life situations. The basic elements of a ministerial model are:

- focus on a specific setting or field, generally a human need, or a human group, or a life situation;

- proclaim and flesh out the truth of the kerygma and the Kingdom of God;

- being based on both human abilities and talents, and gifts of grace;

- discerning and collaborating with the work of the Spirit, already operating in history;

- being the expression of the life and service of a Christian community, sacrament of Chtist’s presence and action in the world;

- generally mission requires a plurality of services and competences, hence the need for collaboration.

In such a perspective, and taking into consideration the profound changes in the world, it is clear that JPIC, inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue emerge as cross cutting dimensions of mission. Rather than looking at them as new specialised services, we need to appreciate them as constituent parts of any missionary commitment.

In the spirit of the XVIII Chapter, the requalification along ministerial lines of our missionary service requires, as Comboni realized, a new “structure” of the mission that sustains and fosters it:

• a ministerial requalification of our commitment, with a ministerial plan that is shared and made in communion, for specific pastoral priorities, in accordance with the continental priorities. During the Chapter, it emerged that, on the one hand, we are present in these “frontiers” of mission while, on the other hand, we often lack a contextual approach to the human groups we accompany;

• collaborative ministry along paths of communion. We are still subject to practices and ways of operating that are too much individualistic and fragmented;

• re-thinking our structures while seeking greater simplicity, more sharing and the ability to welcome others, so as to be closer to the people, more human and happier;

• all this with the reorganisation of the circumscriptions. Merging does not find its justification only in the shortage of personnel, but rather, it has a value in relation to the passage from a geographical to a ministerial model which makes it necessary to be connected, to work as a network and to share resources and approaches;

• the reorganisation of formation to develop the necessary expertise in the various specific pastoral fields.

In brief, as Chapter Acts state, “the growing awareness of a new paradigm of mission spurs us on to reflect and re-organise our activities along ministerial lines.” (CA 2015, No. 12). As invited by Pope Francis (EG 33), the Chapter has indicated the path of pastoral conversion, abandoning the criteria: “as we have always done” and setting in motion a series of action-reflections to reconsider the goals, structures, the manner and method of evangelization (CA 2015, No. 44.2-3).

For example, as our Ratio Missionis pointed out, a ministerial approach requires to:

= contextualise our missionary commitment according to the reality of the people where we live (pigmies, afro-descendants, pastoralists, city slums etc.);

= being present with the people, in the sense of ‘making common cause’ with the people and ministering in fidelity to the context;

= discern the signs of the times and of the places: missionary work has different ways of being carried out, depending on the historical circumstances and people’s life and context.

The challenge of our time and the Laudato si’ Action Platform

Pope Francis has indicated the path of mission as the fundamental pattern for the Church of our time, in his Encyclical Evangelii gaudium. Soon after, with Laudato si’, he has also reflected on the major global issue of our time, namely, that of integral ecology and a sustainable world. Unless current trends in terms of climate change, environmental devastation, and social exclusion are reversed by the year 2030, we shall reach a point of no return. Pope Francis calls for a conversion, underscoring that behind the structures of sin responsible for the unsustainable situation there is an anthropological crisis, that is, a fallen outlook on humanity and Creation, divorced from God. Thus, the commitment of the Church to conversion to integral ecology is urgent not only because of the dramatic situation of the world, but also because of her vocation as sacrament of communion with God and unity of humanity and the whole of Creation.

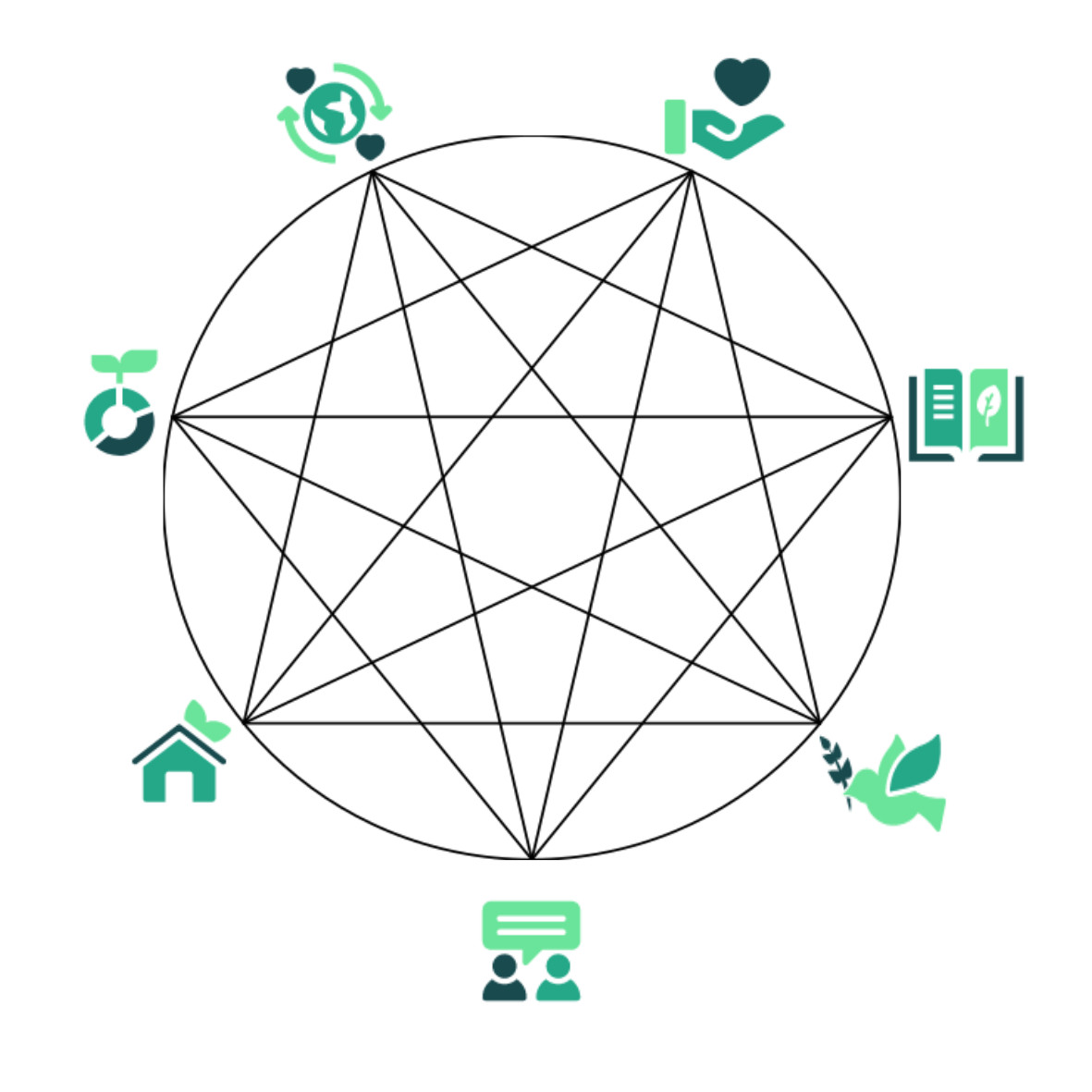

As Laudato si’ reminds us, “interdependence obliges us to think of one world with common plan” (LS 164): in other words, it is not enough to give life to beautiful initiatives, but it is also necessary to connect all these experiences, to have them form a system in order to influence the global reality effectively. Hence the call for a Jubilee for the Earth, a profound personal, cultural, and above all structural conversion. It is the system that must change, and the Church wants to be among the protagonists of this change. For this reason, the Dicastery for Promoting of Integral Human Development is devising a plan for the implementation of Laudato si’ which aims to make all Catholic communities in the world sustainable in the spirit of integral ecology by 2030. This is known as Laudato si’ Action Platform, which defines 7 Laudato si’ Goals (LSG), the common horizon of all Catholic communities: these are

= Respond to the cry of the poor

= Respond to the cry of the Earth

= Ecological economics

= Adoption of simple lifestyles

= Ecological education

= Ecological spirituality

= Community engagement and participatory action.

This is the overall framework worked out by the Dicastery:

= It will be officially launched on May 24th, 2021.

= Participating communities and Institutes, commit themselves to a 7 year journey to complete their transition to Integral Ecology.

= However, it is hoped that new communities will join the initiative every year.

= In fact, to allow for an exponential growth, the intention is to at least double the number of participants every year.

= That would lead to the growth of a Laudato si inspired network of communities.

= in order to reach quickly a critical mass (3.5% of a population) for radical transformation. That is necessary for systemic change. In fact, social scientists tell us that when 21-25% of a population embraces change, then the social system will change.

The Religious are asked to look at their sphere of influence and determine their planning. It is an opportunity to make a contribution informed by their own charism to the common effort for integral ecology; and so they can also energise their specific mission as they respond to the cry of the Earth and of the poor. By doing so, they actually end up requalifying their ministerial service, and, on the other hand, they participate in shared responsibility for a sustainable world and contribute to the synergy that will take us there.

In response to the cry of the impoverished and of the Earth, today Christian communities are called to develop social ministries with creativity. Their strength and originality in the social sphere lies precisely in their commitment, fruit of the common and synodal journey of faith, in listening to the Spirit. In a world now plural in terms of cultures, cosmovisions and religions, we are called to dialogue, to discover the seeds of the Word, the presence of the Spirit in wisdom, to get to know indigenous peoples and to develop a reciprocal maieutic. Ministeriality emerges in keeping in tension the scientific-professional dimension of the commitment to social transformation with that of ethics, of values, of the sense of the common good and of the common home, of a vision of a sustainable, equitable and fraternal world.

Celebrations are privileged moments in which these dimensions are encountered: the liturgical dimension that anticipates the final transformation by celebrating it, making it present even if not yet fully present, is an example of this. It is a profoundly transformative moment, above all of the heart, perspective, attitudes and basic choices, not only on a personal level, but also on a community level: a particularly fertile area of regeneration, of conversion, an essential requirement for any transformation; a moment of grace mediated by the Word and the sacraments. At certain times of the liturgical year, such as Lent for example, there is the possibility of helping Christian communities to make a particular journey of conversion, as the recent Synod for Amazonia has also called for on several levels at: pastoral, cultural,ecological and synodal levels. In an increasingly conflicting and violent world, it is also particularly necessary to rediscover and develop the social dimension of the sacraments, such as that of reconciliation.

Also, with regard to this aspect, a dialogue with the living traditions of peace and reconciliation of indigenous peoples opens interesting avenues for research in the line of interculturality and inculturation for social transformation.

Conclusion

When considering mission from the perspective of the Comboni Missionaries today, it is necessary to contemplate both the journey and discernment of the Institute over the years, and the journey of the Church as well. In fact, these two aspects are interconnected, in dialogue and attentive to the signs of the times and the invitations of the Spirit.

As an Institute, we have been discerning the path of a ministerial approach to mission:

= Overcoming the geographical paradigm: although mission happens within specific geographical boundaries, it is viewed as driven by a new awareness of the context and people’s situations, and the necessary discernment of the signs of the times.1

= A second dimension is the discovery of diversified methods of evangelization: we became aware that each missionary context has a direct influence on how mission was conceived and its methods.2 Ratio Missionis underlines that missionary work has different ways of being carried out, depending on the discernment of historical circumstances and people’s life and context, and it asserts the importance of being present with the people in the sense of ‘making common cause’ with the people, choosing the poor and sharing their reality, and pastoral activity carried on in fidelity to the context and to the various missionary situations in which we find ourselves.

= The Institute, following II Vatican Council, is aware of the fact that mission is a commitment of all the local forces, in communion with the whole Church. Mission, that is, is built on collaboration. The Institute understands that community life is essential to missionary work and that mission determines community life and forms its identity status (‘evangelising community’).

= The XVIII General Chapter (2015) sanctions that the growing awareness of a new paradigm of mission spurs us on to re-organise our activities along ministerial lines. The Chapter suggests some of the specific pastoral services, according to Continental priorities and shared by various Circumscriptions, with the necessity to collaborate at provincial and interprovincial level. There is a need to network (Comboni Family, other pastoral agents, Organisations, centres of reflections and research) and share personnel and skills.

= Ratio Missionisunderlines the importance of a ministerial Church and the need to recognize the lay people’s ministries. There is the awareness of a change of mission paradigm whereby mission is lived out in a plurality of dimensions and services.

All such indications are confirmed in the vision and guidelines of Evangelii gaudium, the programmatic encyclical of pope Francis that presents the new paradigm of mission as the model for the pastoral work of the Church. In this Letter, pope Francis relaunches the theological vision and ecclesiology of Vatican II and charts the trajectory of the Church for the years to come.

A trajectory that cannot be indifferent to the fundamental challenges of our time, as they are presented in the encyclicals Laudato si’ and Fratelli tutti: in fact, “we are not facing two separate crisis, We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both social and environmental” (LS 139). They call us to assume the prophetic role that Religious life and our charism confer upon us. That does not mean to add new commitments to what we are already doing; rather, to undergo a radical conversion that transforms our lifestyle, community living and missionary ministry. It is an epochal opportunity to undertake that requalification of our mission which we have been longing for for decades, but we have not yet been able to roll out as yet. This is the kairos, the favourable to time to embrace it.

End notes

1The Chapter of 1969 saw that “[geographical and legal criteria] although they had the advantage of clearly distinguishing missions from non-missions, are no longer sufficient” (AC ’69 II, 56). The Comboni charism is freed from purely geographical criteria in favour of an essentially missionary perspective: that is, evangelization ad gentes must take “into account first of all [the] different peoples and [the] different groups of cultures”. The Chapter of 1975 takes into account “frontier peoples, i.e. tribes, ethnic or social minorities and other minority groups who are not yet evangelized and have remained on the margins of the current evolution of the world “(II,14).

2The 1985 General Chapter acknowledges that different “missionary situations” require different priorities and different services, that is, every missionary method must be adapted to the context.